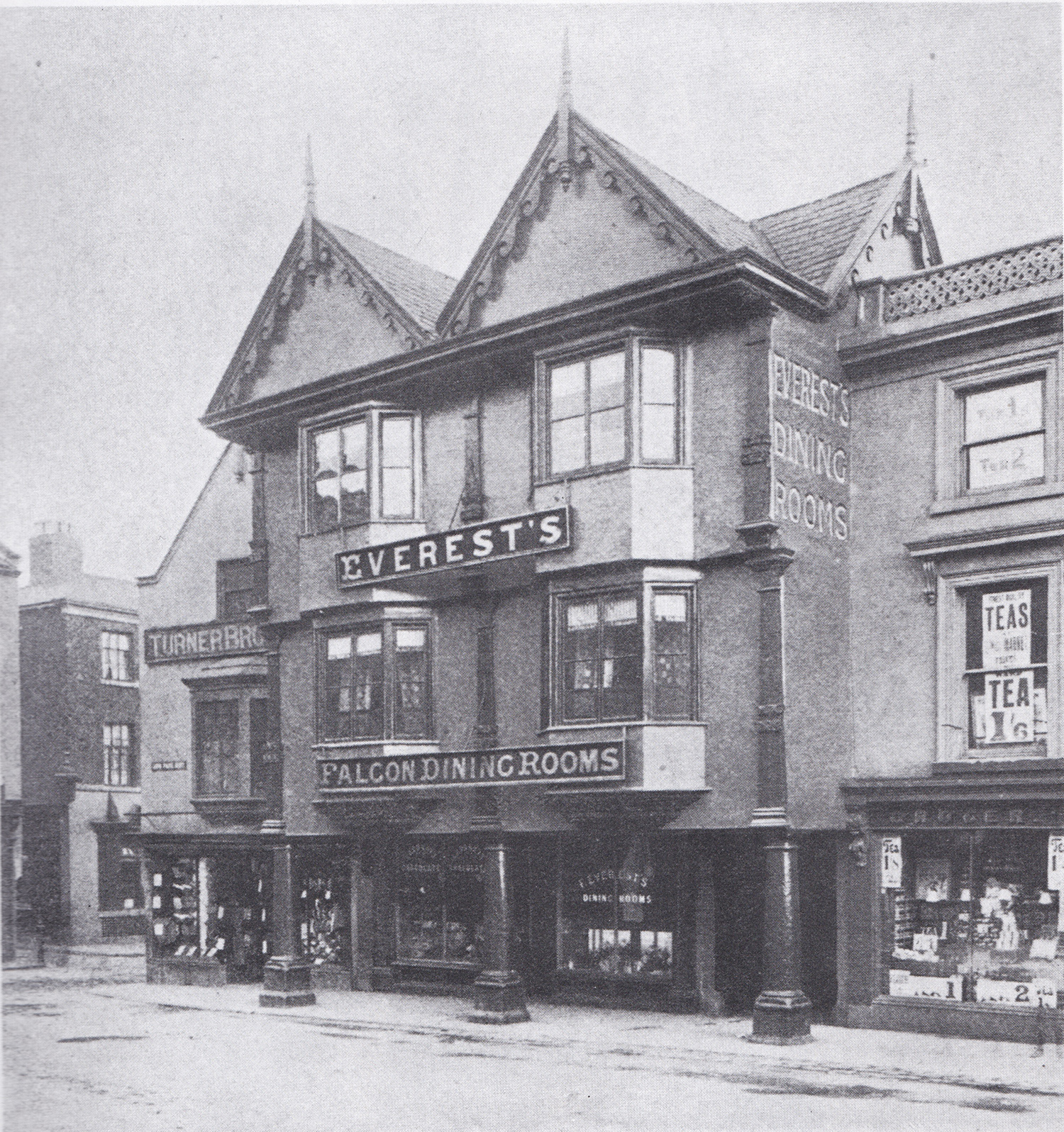

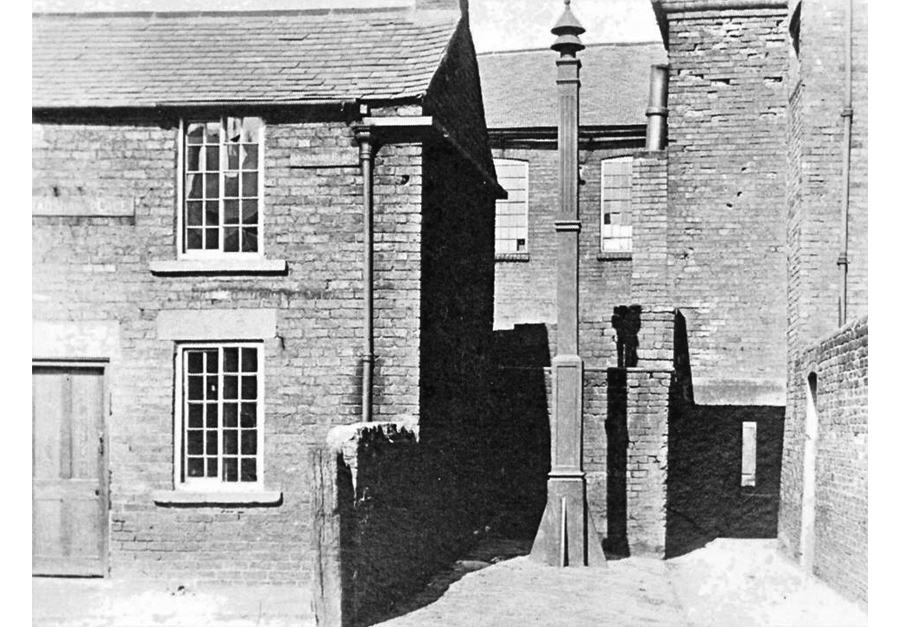

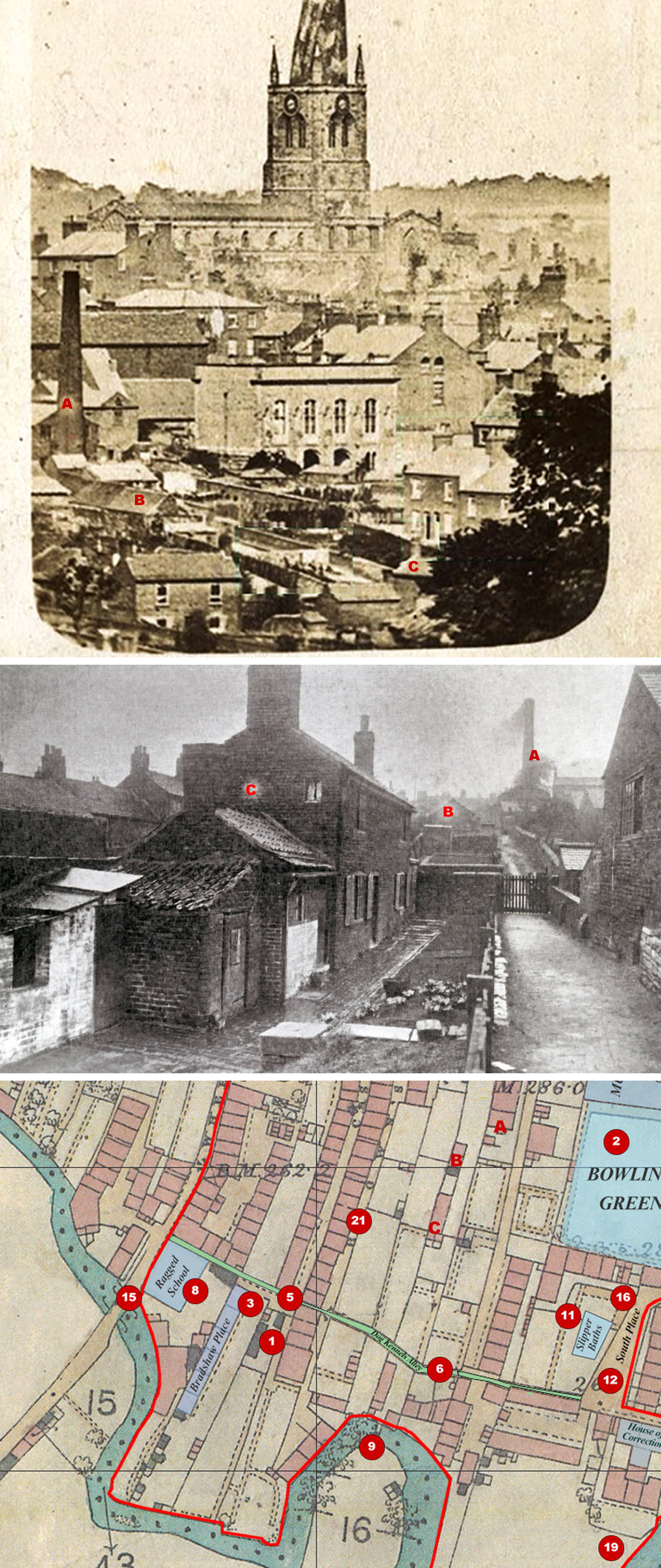

The House of Correction or the Lock Up in Nov 1912 just before demolition. The building was erected, in 1614 on the banks of the River Hipper – The tall chimney of the Silk Mill can be seen behind.

(Courtesy of Jane Kirk)

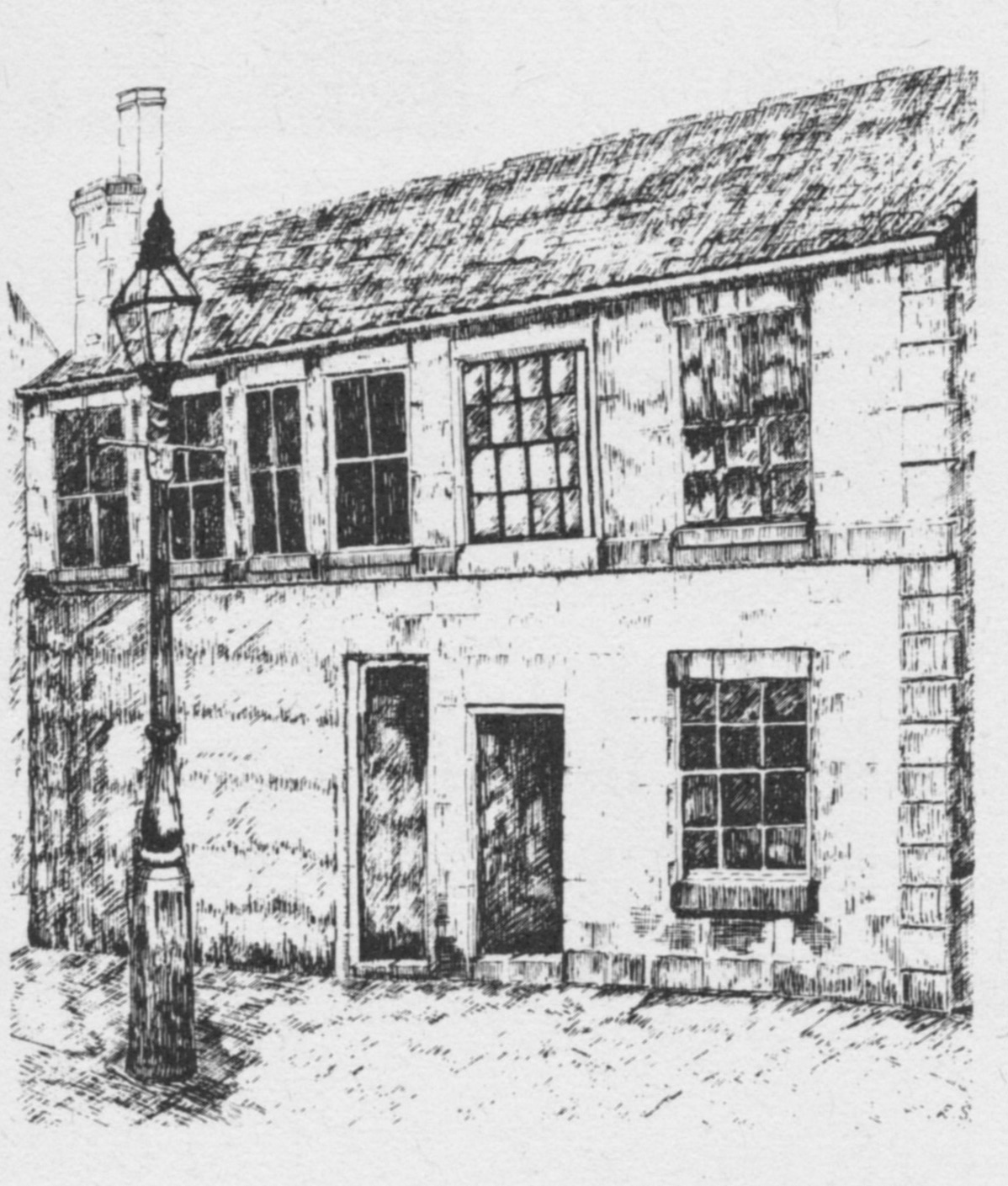

Drawing by Elsie Cannam

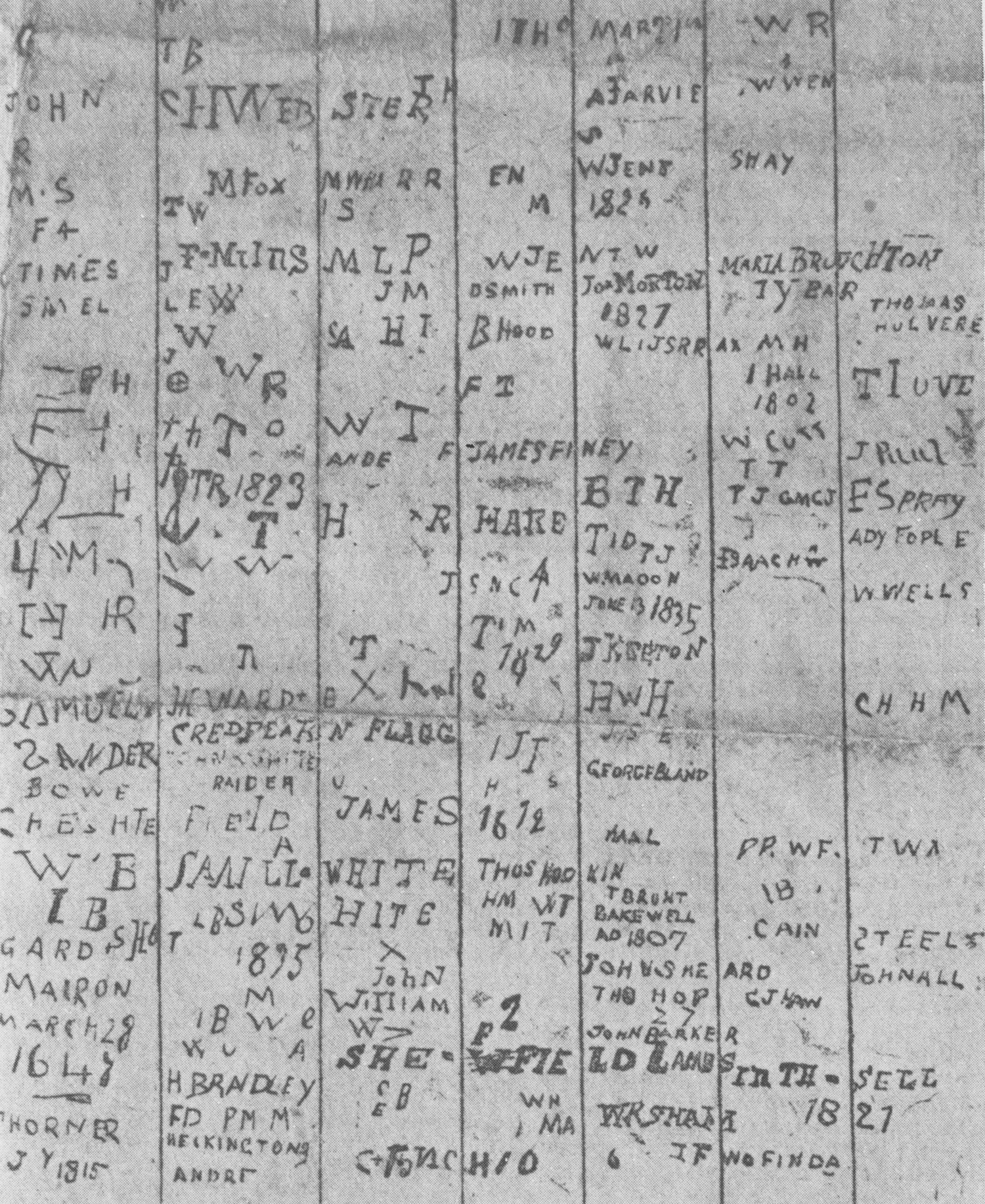

Prisoners carved their names on a door in the House of Correction

Prisoners carved their names on a door in the House of Correction

We have found a few references to the House of Correction, most of them very brief.

The first:

“In the early 1830s this court met annually in October before the Steward of the Manor, John Charge, a local lawyer who presided from 1818 to 1841 and who in 1830 became Clerk of the Peace for Derbyshire. A Grand Jury and Petty Jury were sworn in and it was they who nominated two men to serve as Constables and usually three as Assistant Constables. The Constables normally served for two years, one new appointment being made each year, but the Assistant Constables tended to remain in office for several years. The only other old manorial offices still being filled at this date were those of Pinder and Beadle. From 1831 to 1835 they were filled by John Bower, who was also an Assistant Constable and gaoler at the House of Correction. During these years the cases considered by the court arose from breaches of a small number of the bye-laws and were to a remarkable degree concerned with annoyances and dangers arising from the neglect of buildings.”

History of Chesterfield Vol III byJM Bestall & DV Fowkes

The second reference:

Not only the lady of quality, but her more plebeian sister, had a tendency to erratic conduct and especially to prating. There is a saying that “a woman will have the last word,” but formerly she had both the first and the last, and in self-defence the men, barbarous and unsentimental, no doubt, fashioned a ducking-stool and placed it in the Silk Mill Dam, with the object of taming all shrews. A bad- tempered woman, sitting in the chair that was plunged into the water with every dip of the cross-beam, had a wet time of it, and a rhymester, who had possibly married a virago, chuckling at her plight, wrote :—

No brawling wives, no furious wenches,

No fire so hot, but water quenches.

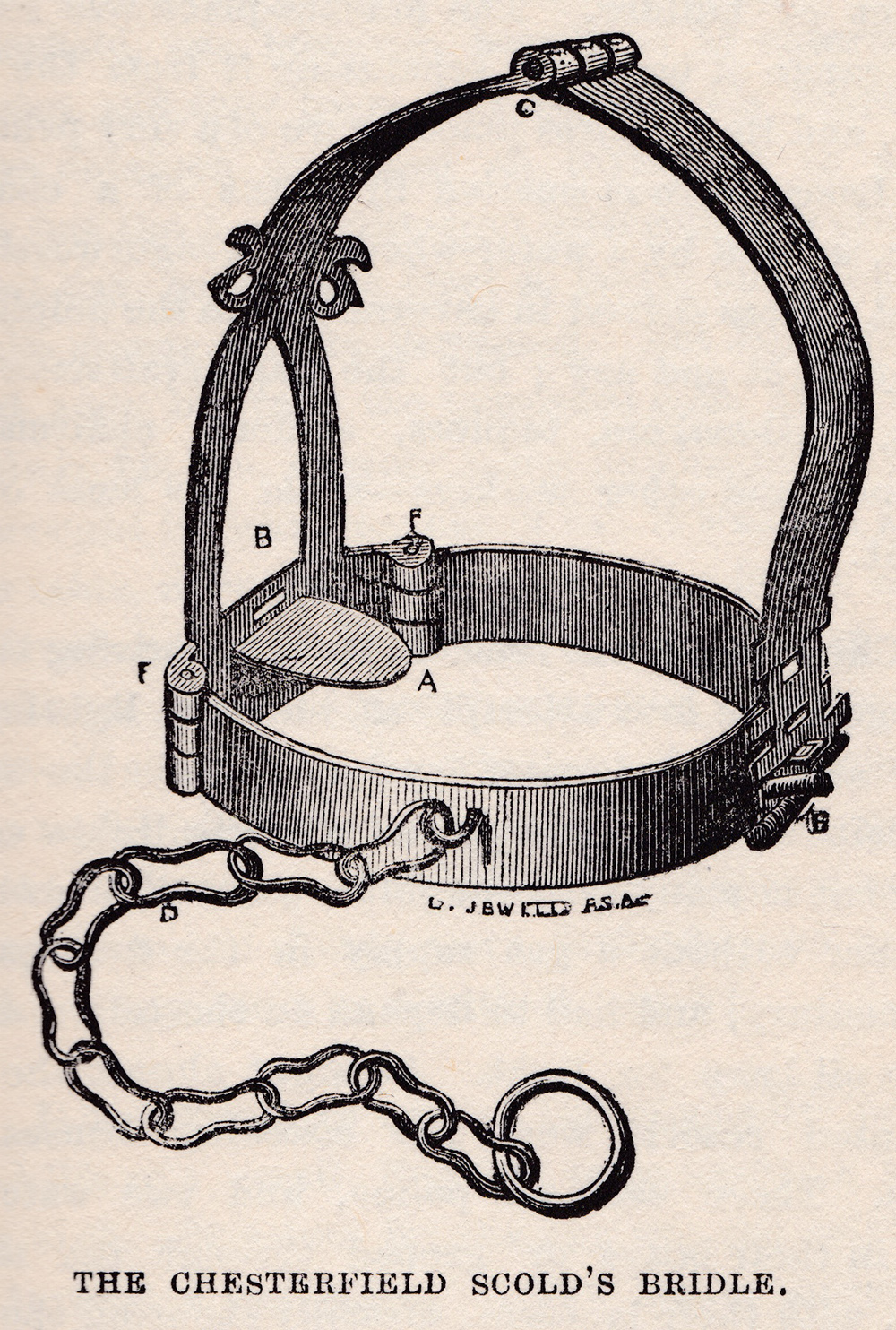

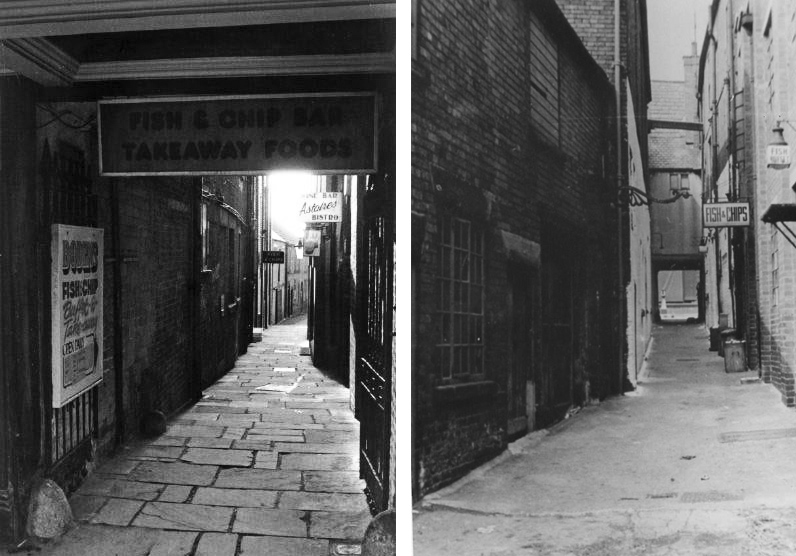

The poorhouse and the old prison were in South- place, near the Silk Mill and the ducking-stool, and it is said that not only scolding wives, but female prisoners and refractory paupers were subjected to the cleansing virtues of the current that sped to “ the shuttle.” Dr. Johnson, who classified our language, was also a stickler for discipline and remarked to a lady : u Madam, we have different modes of restraining evil—stocks for the men, the ducking-stool for women, and the pound for beasts.” Yet it seems incredible, in an age ot political and social freedom , that the ducking- stool and the scold’s bridle, or iron headpiece that kept a woman’s tongue absolutely and cruelly still, should have remained so long in use.

The prison, or lock-up, as it was called, is now a beerhouse. Its thick walls and barred windows were apt to foster awe in the youth of the town, and its cells, even in Superintendent Radford’s time, safe- guarded many a desperado. Politely styled “ The House of Correction,” it was undoubtedly a corrective the most boisterous breakers of the law, for it was damp, dark, and gruesome enough to yield scene for weird story.

The prison, or lock-up, as it was called, is now a beerhouse. Its thick walls and barred windows were apt to foster awe in the youth of the town, and its cells, even in Superintendent Radford’s time, safe- guarded many a desperado. Politely styled “ The House of Correction,” it was undoubtedly a corrective the most boisterous breakers of the law, for it was damp, dark, and gruesome enough to yield scene for weird story.

Modern Chesterfield by John Pendleton & William Jacques

The third reference:

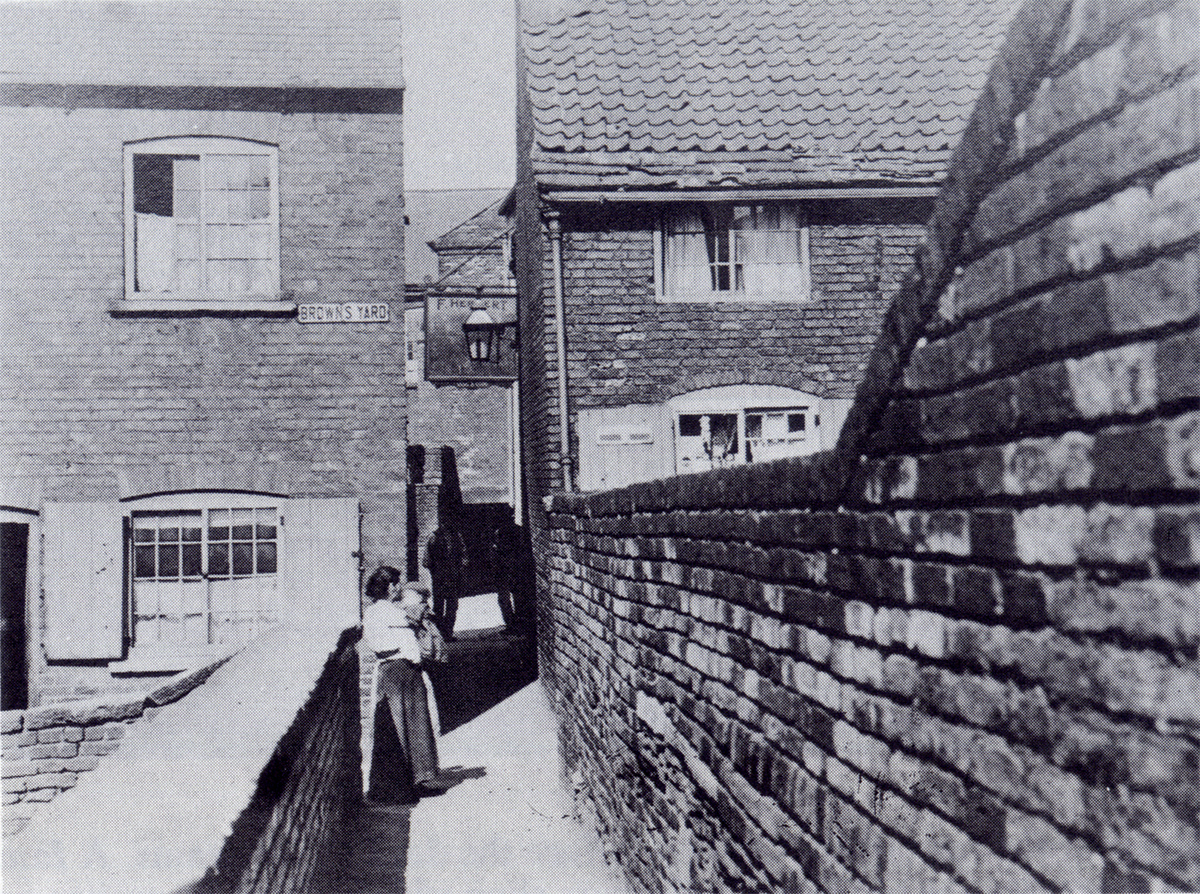

Possibly on the assumption that there is some affinity between pauperism and crime, the old House of Correction was situated within a stone’s throw of the poor house. The lock-up, as it was familiarly called by its most frequent visitors, was erected in 1614, on the north bank of the Hipper, opposite the Silk-mill, at the bottom of South Place. The approach to it, past the Bowling Green, and along the once narrow walk beyond, has been the scene of many a fierce fight, in which the police were usually the conquerors. The old building, with its thick walls, and heavily- barred doors, has been the temporary home of many notorious criminals, some of whom scrawled strange legends on the cell sides, to while away the dreary hours of their captivity. Years ago, Mr. Hollingsworth used to be the gaoler; then Superintendent Radford lived there; and now, the old prison is – a beer-house!

Old & New Chesterfield by Tatler

The fourth reference:

The House of Correction

This building was erected, in 1614, in a low damp situation, on the bank of the river Hipper, the worst place that could be found for such a purpose. It is under the superintendence of the magistrates of the hundred of Scarsdale, but is too small to admit of the classification of prisoners. When the question concerning the removal of the Midsummer Sessions to Derby was discussed, it was proposed to discontinue the House of Correction at Chesterfield; but that project was abandoned. Mr. Hollingworth is the present gaoler.

The History of Chesterfield and descriptive accounts of Chatsworth, Hardwick and Bolsover by George Hall 1839

The fifth reference:

A gaol is mentioned as early as 1196, when the King as Lord of the Manor authorised the expenditure of £6 13s 4d for its maintenance. It served the whole Wapentake of Scarsdale, as a short term lock-up, and other records show that prisoners were moved to Nottingham and Peak Castle. In 1658 it was under the Moot Hall; in 1788 it was replaced by accomodation on the ground floor of the new Town Hall.

A “House of Correction” for minor offenders was built about 1615 in the Cockpit Yard. It was to accomodate prisoners from Scarsdale and the High Peak. It is shown on the survey of 1633, and described by by Ford, in 1839, as being ‘in a low damp situation on the bank of the river Hipper.’

“The Book of Chesterfield” by Roy Cooper

You must be logged in to post a comment.